The incidents of 1971 which happened in former East Pakistan take up inadequate room in Pakistan’s literary canon. But one is hard-pressed to find robust short-stories and novellas with the exception of Masood Ashar – who passed away last year – and Masood Mufti.

While depicting that period in poetry, we repeatedly cite the one ghazal by Faiz Ahmad Faiz, ‘Hum ke thehray ajnabi’ (We who stayed strangers), and some other poetry spread here and there that endeavours to take in or responds to that humongous human calamity.

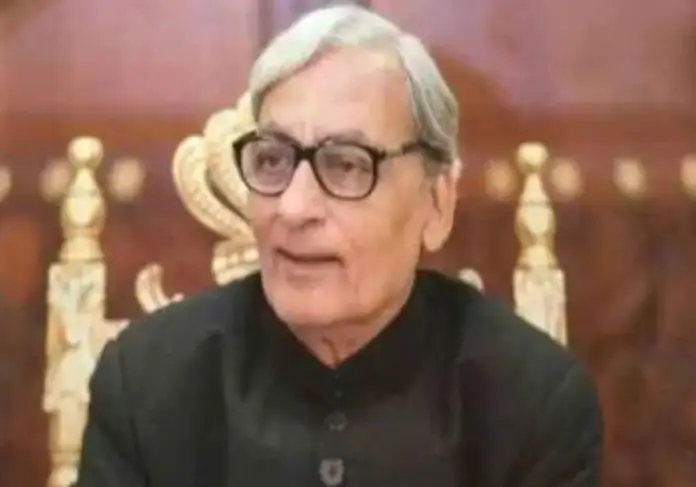

However in December 1971, another ghazal was penned, which consists of remarkable verses on the Fall of Dhaka. What is paradoxical and interesting at the same time is that this very ghazal is today renowned as the official sound track of one of Pakistan’s most watched private television dramas, the focus of which is a three-pronged love affair. ‘Voh Humsafar Tha Magar Uss Se Humnavai Na Thi’ (He was a fellow traveller but we did not speak in unison) is the ghazal penned by Naseer Turabi – who passed away unexpectedly a year ago today at the age of 75 – on December 16, the day Pakistan was dismembered.

It’s paradoxical that a prompt, imaginative reaction to a momentous incident has turned into a well-known melody because of an average tearjerker. But maybe it is also a tribute to the totality of creative communication in its higher manifestation. The various strata of feeling, the grave sensibility of banality, repentance and regret elevate this ghazal to a degree where it can be prized by a person and an entire country in totally contrasting, but matching ways. On second thought, the contention between the three South Asian brothers of Joseph – Pakistan, India and Bangladesh – could be taken as a three-prolonged love affair.

Turabi worked in both Urdu and Farsi with a language imbued with the long-established custom of these languages and a sense benefitting from Indo-Persian civilization. However he utilized a totally novel expression so that he could share an accepted trope with a modern reader. Because bows and arrows and quiver are generously deployed as metaphors in our verses, one can appropriate these metaphors to say that Turabi’s quiver of verses overflowed with such arrows of incisive verses that prick a reader’s heart.

Whether it is his ghazal collection ‘Aks Faryadi’ (The Supplicant’s Reflection, 2000) or ‘Laraib’ (Certainly , 2017) – a volume of spiritual verses mostly honouring the offerings of the House of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) – his couplet had a decisive attribute and solid cultural berths.

Turabi was more performed than recognized. First-rate performers, like Abida Parveen, have sung and promoted his oeuvre. He was also admired by listeners in mushairas and cultural events locally and internationally. However he was yet to earn his due stature from literary commentators.

He was from that scarce and diminishing lineage of our versifiers who triumphantly married the old with the new, not only with reference to diction but also his preference of topics. In addition, he was one of the rare ones left in our midst who wrote in Farsi too. That was the custom of virtually all our long-established poets of yore. However matters have altered with reference to our semantic and aesthetic preferences, detaching us from Farsi and its substantial artistic heritage. This detachment is a consequence of the dogmatic posture and political arrangement of our national state that emphatically rejects the aesthetic history of subcontinental Muslims.

To conclude, what heightened Turabi’s stature to a scholarly versifier, in contrast to being just merely ‘a versifier’ is his tome ‘Sheriyaat’ (poetics), which was originally published in 2012 and has been republished many times since then. Both erudite and approachable simultaneously, the volume describes foundational concepts, shapes, jargon, enunciations, vocabulary, and the inaccuracies engaged in penning Urdu poetry.

Turabi’s oeuvre had a perceptive touch, which courses through his verses as well as non-poetic works.