Gramsci, whose mother

considered her son

the state’s enemy number one

Anti-utopian of universal equality,

theorizer of the new society,

you are no martyr, Gramsci,

just an organizer

accelerating

the revolution

rooted in reality.

(Antonio Gramsci, Rebecca Ruth Gould)

January 21 was the 101st anniversary of the foundation of the Communist Party of Italy, the party which was founded under the worldwide vision of Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the world’s first successful socialist revolution in Russia, whose 98th death anniversary was incidentally also observed yesterday. It was outlawed soon after by the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini before making a comeback as the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1943 after the fall of fascism.

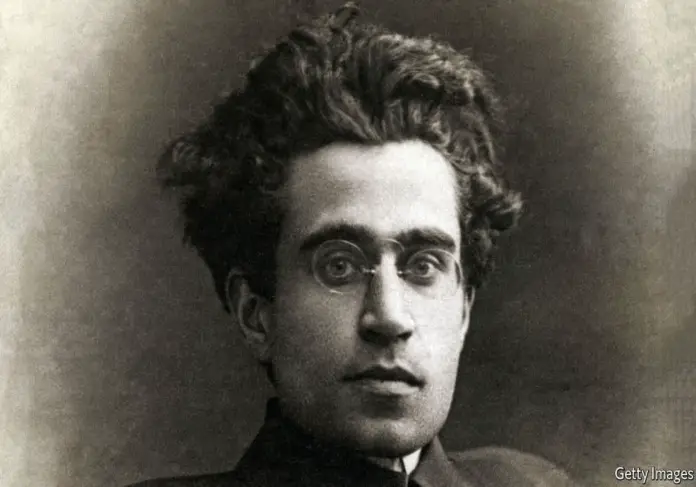

One of the founders of the historic Communist Party of Italy was Antonio Gramsci, who was born on January 22, 131 years ago.

When Gramsci was brought before the fascist courts to charge him, those who tried him famously declared that they were required to prevent his mind from working for two decades. Consequently he was given 20 years internment by Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime.

Mussolini’s prosecutors nearly got their wish; however jail developed rather than declined Gramsci’s thinking. He set out on a breathtaking, if lonely path to intellectual inquiry, and as we now know, immortality. For in jail, he composed his Prison Notebooks, consisting of 33 books and 3,000 sheets of history, philosophy, economics and revolutionary theory. Despite having permission to write, Gramsci’s access to Marxist literature was cut off and he was compelled to write in code words to elude the prison authorities. He eventually passed away in 1937, weakened by inadequate health care and physical deformities.

But in death, he left an enduring legacy which he cherished in his lifetime. His Prison Notebooks were sneaked out by his brother’s wife Tatiana and published in Italy in the period 1948-51. He is at the moment cited frequently by pundits across the political divide who remember his most unforgettable maxim and his pithy delineation of the 1930s: ‘The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.’ How to explain Gramsci’s odd, disputed afterlife in our own times?

The most significant idea for which Gramsci is recognized today is hegemony. This implies an extent of political dominance going past the authority of a state or legislature. Gramsci was engrossed by the issue of why Russia was the sole European state where a revolution was successful in the 20th century. He gave an answer in the tenacity of capitalist concepts among civil society organs (parties, trade unions, churches, the media). In his own words: ‘The state was only an outer ditch, behind which there stood a powerful system of fortresses.’

Gramsci believed that it was not enough for communists to fight a ‘war of movement’ (exemplified by the successful Bolshevik Revolution in 1917), rather they had to engage in a ‘war of position’, that is, a long-term tussle in the field of civil society with its objective to transform ‘common sense’, in Gramscian terms.

In the south Asian subcontinent, Gramsci’s analysis is particularly prescient when we look at the march of populism with a religious-fundamentalist colouring. Just like the Marxists in the UK and across the Atlantic came up with trenchant critiques of the rise of Thatcherism and Reaganism in the 1970s using Gramscian lens, Marxist theorists like Aijaz Ahmad turned to Gramsci to explain the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party in India in the 1990s with the end of the Nehruvian socialist state at the same time. Those analyses now strike one as frightening and accurate as one surveys the march of creeping Hindutva through the Indian body politic following the fracturing of Congress as well as Indian communism as viable opposition alternatives and the rise of Narendra Modi in recent years.

In Pakistan too, the rise of the populist forces in the form of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and Prime Minister Imran Khan, as well as the new right in the form of the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) have validated renewed interest in the memory and legacy of Gramsci in Pakistan. There has also been a rise of new social movements in Pakistan in recent years, which have catalyzed around movements like the Students Solidarity March, the Aurat March and farmers, doctors and lady health workers’ struggles which reward and repay looking at these anew through Gramscian analysis.

One can indeed be forgiven for believing that Gramsci’s idea of hegemony feels refreshingly current in the 21st century. Thus he increasingly looms over the intellectual and practical horizon as not merely a communist intellectual for the now, rather as the only one.

80 years after his death we are grateful to Gramsci not only for intellectual stimulation, but for teaching us that the effort to transform the world is not only compatible with original, subtle, open-eyed historical thinking but impossible without it.

And as Gramsci himself wrote in the famous letter of September 1931, outlining the main themes of his political theory:

My study of the intellectuals is a vast project…I greatly extend the notion of intellectuals beyond the current meaning of the word, which refers chiefly to great intellectuals. This study also leads me to certain determinations of the State. Usually this is understood as political society (i.e. the dictatorship of coercive apparatus to bring the mass of the people into conformity with the type of production and economy dominant at any given moment) and not as an equilibrium between political society and civil society (i.e. the hegemony of a social group over the entire national society exercised through the so-called private organisations such as the Church, the trade unions, the schools, etc.) Civil society is precisely the special field of action of the intellectuals.’

As Pakistan teeters between talk of a presidential system and the fallout from just the latest incident of terrorism a few days ago in Lahore, let me conclude with one of my favourite quotes from the Sardinian working-class rabble-rouser, which provides full context for his aforementioned ‘unforgettable maxim’:

On daydreams and fantasies. They show lack of character and passivity. One imagines that something has happened to upset the mechanism of necessity. One’s own initiative has become free. Everything is easy. One can do whatever one wants, and one wants a whole series of things which at present one lacks. It is basically the present turned on its head which is projected into the future. Everything repressed is unleashed. On the contrary, it is necessary to direct one’s attention violently towards the present as it is, if one wishes to transform it. Pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the will.

(‘The Prison Notebooks’, 1932)