Now I have no land, no country, the town named Behrampur is still located in India at that very place but it is devoid of spirit. That is not my country. Sacramento is not my country. Chak number 57 is not my country. I have been running for the last 50 years; continuously been running day and night and have reached where there is neither my home, nor country, nor any loved one nor any relative. I am sitting alone. I deem the whole world to be my country and the whole humanity is my relative. The world is, so to speak, a railway train whose carriages are overflowing but a few are empty too which have a few passengers present. They have shut all the windows and are standing packed within the doors. Passengers wandering to search for space on the platform are disallowed to touch even the door. Baba! There is no space here go further. This is a reason for misdeeds based on selfishness. Every living thing on the Earth has the right to live in every country. The law of nationalities and citizenships has become old and useless. Keep every country of the Earth open for everyone. Do not put restrictions. Who are you anyways?

These could very well have been the thoughts of any of the four members of the hapless Patel family, found frozen to death near the US-Canadian border last week. On their long trek from their native Gujarat, they have become yet another statistic, caught up in the familiar web of human trafficking and illegal migration.

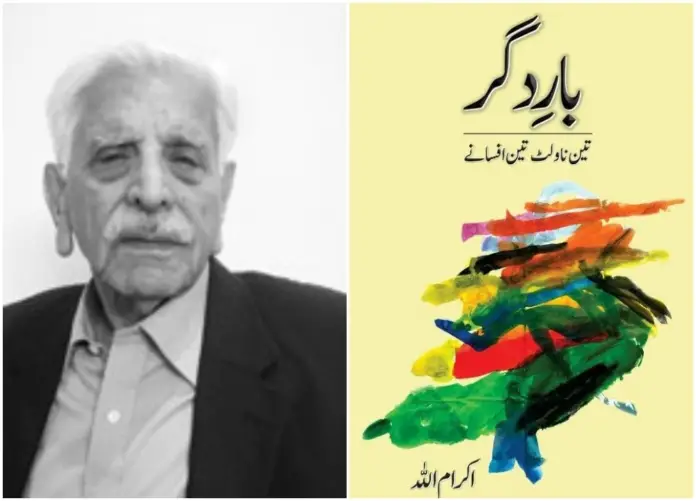

As I read of this human tragedy, I was reminded of the novella Diyaar-e-Ghair (Alien Soil), part of the latest book of short-stories and novellas titled Baar-e-Digar (A Second Time, Sang-e-Meel Publications, Lahore, 2021, 216 pp.) by the distinguished Urdu writer Ikramullah, who is celebrating his 93rd birthday today. Ikramullah weaves a complex tale of migration and its discontents in the united Punjab of the early 20th century, which begins when one of the protagonists Allah Bakhsh journeys from Behrampur in Jalandhar to San Francisco to join his Sikh friend Gurbaksh in the vineyards of California’s historic Napa Valley as they attempt to make the desert bloom with the sweat of their labour.

The story of Punjabi migrants to the United States is one of the hidden histories of 20th century migration. While everyone has heard of the Chinese and Japanese inter-war migration in the 20th century, the full story of how Punjabis left their ancestral lands to make the arduous journey to North America and struggled to assimilate in a closed and racist society where what to talk of black men, even Asian men were not allowed to marry white women unless they were willing to brave the death penalty, is yet to be properly documented. Faced with rampant immigration from the Punjab, the US put in place laws, which not only forbade the new migrants from owning any land in their newly-adopted homelands, but also decided they were not the right skin-colour to be classed as Caucasians. These exclusionary laws – not dissimilar to the laws currently put into place by some Gulf states for their own Asian migrant labour – together with the caveat that the Asian migrants were prohibited from bringing their wives from home were the harbinger for subsequent racial and political discrimination. In Ikramullah’s deft hands, the novella does not just become a dry history lesson for the 21st century but authentically speaks for the dispossession of the Punjabi migrants. In a telling passage, Allah Bakhsh bears witness as follows:

I saw that in California every Punjabi carries his Punjab full-time upon his shoulders without discrimination of faith. The other Punjabis try their best to supply Punjab to him on a linguistic, cultural and social basis and this aid is mutual. He feels himself in California only when he receives salary or remuneration in dollars; the amount which has to become inflated further after reaching back home. Other than this he is very much living in Punjab all the time; that Punjab which is changing every second subject to the law of nature. When he returns, the Punjab which he had left behind will not be there. The truth is that the feet which have been uprooted from home once, are not fated to re-enter that land. The wanderer forever very much remains a wanderer.

The contrasting lives and fates of the two protagonists of the novella are expertly weaved into the experiences of the real-life Ghadarite Pakher Singh Gill who was one of many Punjabi Sikh migrants to California’s Imperial Valley at the beginning of the 20th century and helped in making its unyielding land bloom, yet confronted the discrimination and thuggery of their American landlords in a judicial case which galvanized farm workers across the race divide in the 1920s US; and ‘gentlemen’ like Dalip Singh Saund, who voluntarily immigrated to the United States around the same time as his fellow-Sikh Gill, graduated from Berkeley and rose to become the first Sikh American, the first Asian American, the first Indian American and first member of a non-Abrahamic faith to be elected to the US Congress.

The writer of this compact novella, Ikramullah, was born today, January 29, 1929 in Jandiala in District Nawanshahr (East Punjab, India). He began his education in 1934 at the Islamia Primary School in Moga, District Ferozepur. Since his father was employed as a doctor in the health department of the Punjab Government, he was appointed in different cities and villages of Punjab, so that Ikramullah’s remaining education was completed in Sillanwali, District Sargodha, Lahore, Amritsar and Multan. After the partition of India, Burewala became his destination in September 1947 and there was a pause in education for a few years. Afterwards, he passed the LLB exam from the Punjab University Law College Lahore in 1955 and started law practice in Multan. In 1965 he assumed the office of divisional in-charge for Multan at the Ideal Life Insurance Company Pakistan. In 1972 it was nationalized, so he was appointed as law manager at the State Life Insurance Corporation in Lahore.

He has had an attachment to Urdu literature all his life. His first short-story Uttam Chand was published in 1961 in Adab-e-Latif Lahore. Then his writings were included in different journals of Pakistan like Funoon, Aaj and Seep. To date, his short-story collections Jangal (Jungle), Badalte Qaalib (Changing Frames), Sava Neze Par Sooraj (Doomsday) and two novels Saaye Ki Aavaz (The Sound of the Shadow) and Gurg-e-Shab (Night Wolf) have been published. A very readable memoir with the title of Jahan-e-Guzran (The Passing World) came out in 2019; it could be called a novelistic autobiography that is simultaneously a blood-drenched document as well as a fable about the uprooting of ideals. A successor volume of memoirs of his years in Multan has just come out with the title of Multan-e-Maa (My Multan). Penguin India has published the English translation of two of his novellas under the title Regret. His collection of novellas Sava Neze Par Sooraj was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award on October 18, 1999 for the best fiction of the year. In 2016 he was awarded with the Presidential Pride of Performance award. He currently lives in Lahore.

Novellas like Diyaar-e-Ghair are valuable micro-histories, which remind readers that all acts of immigration are not hermetic events but are intertwined with the exploitative processes of colonial and imperialist violence.

*All the translations from the Urdu are by the writer.