January 5 united two of Pakistan’s most charismatic political leader and activists, who in their own way shaped the consciousness of millions of their fellow Pakistanis across several decades and many of their struggles continue to shape the present.

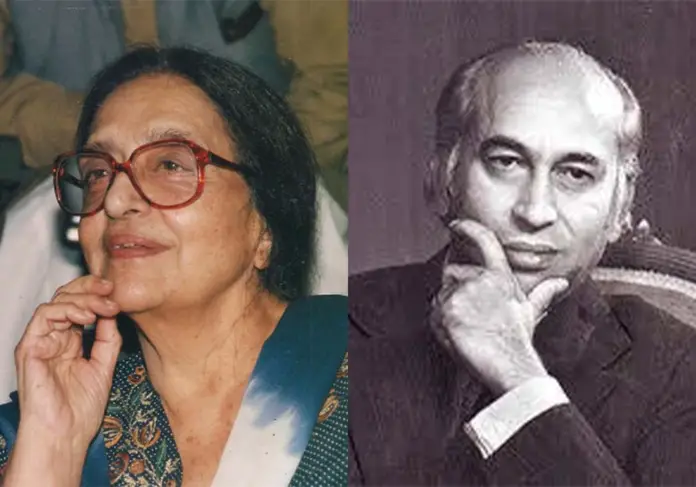

Both the celebrated communist and women’s activist Begum Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan (1924 – 2015) and Pakistan’s former Prime Minister and the founder of one of its two largest political parties Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (1928 – 1979) were born on January 5. Though they fought for the same causes and were contemporaries, friends and even comrades, their legacies and fates could not have been more different.

Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan was born in 1924 in a crusty, feudal family, at the head of which was Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, one of the most powerful landlords in united Punjab, a leader of the Unionist Party and former chief minister of that province prior to partition. Despite being a rival of Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League and later opting for partition, he was a British loyalist. His daughter Tahira though preferred the Congress, with whose leader, Jawaharlal Nehru, later India’s first Prime Minister, she was in secret correspondence with about the battle for freedom as well as reading lists. However, when the headstrong young girl went to deliver a missive from the Communist Party of India – which she had joined upon turning 18 – regarding the party’s position on the partition, she even told off Pakistan’s first governor-general that she supported Congress rather than his Muslim League because the former spoke for all Indian communities and not just for Muslims like Jinnah’s Party.

In her love life, Tahira was as independent-minded as in her politics. She married a cousin Mazhar Ali Khan, who was not only unemployed at the time but a militant Communist sympathizer and student leader, quite contrary to the politics of the immediate family. Naturally, there was opposition from her father but since the couple were in love, they went on with the wedding. Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan was bewitchingly beautiful, even well past her 50s, and must have broken quite a few hearts even after getting married to Khan. I have personally heard this from some older communists during my meetings with them off and on.

Be that as it may, both Tahira Mazhar Ali and her husband energetically immersed themselves in working for the rights of the underprivileged in newly-created Pakistan. Tahira Mazhar Ali was a pioneer of the women’s struggle in Pakistan; she saw no contradiction between supporting women’s rights and workers’ rights at the same time. In fact, she donated her entire dowry to the Communist Party. When we read and write about communism and its fate in Pakistan, we should remember that despite a lot of myth-making, it was the Communist Party of India which supported the demand for Pakistan at considerable risk to itself, while so-called Islamist parties like the Jamaat-e-Islami opposed the Pakistan Movement and Jinnah tooth and nail.

Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan was a vital part of the very first International Women’s Day celebration in Pakistan in 1948, and her home in Lahore was the site for many historic meeting and gatherings, including the formation of the Progressive Writers Association. This was also the period when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB), who hadn’t yet conceived the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), and was in the cabinet of Pakistan’s first military dictator Ayub Khan, befriended Tahira and Mazhar, along with his daughter Benazir.

Tahira Mazhar Ali was also one of the founders of the Women’s Democratic Association (DWA), which was set up in 1950 with the support of the Communist Party to mobilize poorer women and fight for their rights. It was in fact more activist and militant in its support for feminism than the much-touted All-Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA) which had been set up a year before, and was non-political, largely a club of middle-class and upper middle class ladies.

The DWA also played a role in instilling anti-imperialist consciousness within Pakistani women with respect to the raging conflicts of the time like the Vietnamese resistance against US intervention. Unlike ZAB, who was blamed for the dismemberment of Pakistan in 1971, Tahira Mazhar Ali was one among a handful of then-West Pakistanis who protested against the army action in then-East Pakistan on Lahore’s famous Mall Road and were vilified and spat upon as traitors.

Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan also vociferously opposed the draconian legislations of the Zia-ul-Haq regime. In later years, despite her ill-health and the loss of Mazhar Ali Khan in 1993, she remained politically active and present in any and every protest and demonstration for the rights of the underprivileged. She passed away after a long and eventful life on Pakistan Day, March 23 in 2015. As I think of her, I realize that it is a huge tragedy that despite being such a legendary figure of the Indian subcontinent, the present generations have no idea about her historic and heroic struggles, consumed as they are with the narratives coming from the top of ‘great women’ like Fatima Jinnah, Raana Liaquat Ali Khan, Benazir Bhutto and now increasingly, Maryam Nawaz Sharif etc. I dare say that Tahira was no less important than these grandees for she never broke her link with the people. It is about time that a proper biography as well as the struggles of the DWA, which she founded, be written and chronicled, and a major road in Lahore be named after her in lieu of her tremendous services to the cause of her underprivileged people.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, like his contemporary and friend Tahira Mazhar Ali, was born in 1928 in a feudal family which had relocated to Sindh. Unlike the rebellious Tahira, ZAB remained very much true to his class origins until he actually achieved political power himself post-1971. He studied at elite institutions of Oxford in the UK and Berkeley in the US and was a brilliant student and public orator. He began his political career not by advocating for the rights of the oppressed and impoverished, but serving the cabinet of Ayub Khan; he however came onto his own as Pakistan’s foreign minister. It was the Pak-India War of 1965 that made ZAB and unmade his political patron Ayub Khan. As a result of public sentiments aroused by the war fervour, ZAB was exposed to the potential of mass politics, following which he resigned from Ayub Khan’s cabinet and founded the PPP in 1967. The PPP was perhaps Pakistan’s first mass-based political party and ZAB transformed Pakistan’s politics, for better or worse, during the 1970s with the formation of the radically social-democratic PPP, and his slogan ‘roti, kapra aur makan’ (bread, clothing and shelter). Many communists would later complain that Bhutto stole the slogans of the communists to achieve political power. Be that as it may, ZAB, as the leader of the party that had swept to a majority vote in the 1970 elections, first became president and then prime minister of the newly-truncated country a year later. It’s true that under ZAB, some reforms for which Pakistan had been crying for since 1947 were carried out, like land reforms, the reining in of the country’s biggest capitalists, the formulation of the 1973 constitution and the initiation of the country’s nuclear programme. On the foreign policy front, his successful negotiation with India in Simla for the return of 93,000 Pakistani prisoners of war and 5,000 square miles of Pakistani territory held by India after the 1971 Indo-Pak War, and the holding of the OIC Summit in Lahore in 1974 was of significance.

However, his legacy was tarnished by some of his measures like sending the military to shore up his forcible dissolution of a popularly-elected government in Balochistan in 1973 as well as having the Ahmadis declared as non-Muslim in his own Constitution. Both these measures inaugurated unwelcome trends in the body politic of Pakistan like bringing back the army into the affairs of the country just two years after it had been humbled and sent back to the barracks, and injecting the role of religion in democratic matters much before the onset of the Zia-ul-Haq military dictatorship. Eventually, ZAB’s unbridled lust for power, which led to the ouster of several of his key comrades and his attempts to kowtow the army and the clerics led to his downfall in 1977 and eventual execution, leading to such a fracturing of democracy and secularism in the country from which it has yet to recover.

Curiously, Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan and ZAB briefly confronted each other when during the latter’s time as prime minister in 1972, he barred his friend’s son Tariq Ali, the eminent author and activist from reaching Lahore by air. ZAB was fearful of Tariq’s popularity and foolishly considered him a danger to his own survival.

Tahira wrote a severe missive to her friend, alleging that he had let the people down; its intensity compelled Bhutto to rescind the travel ban. While he was in a Lahore jail facing trial after his deposition by Zia-ul-Haq, she had a cigar box delivered to him as a gift, perhaps an appropriate offering from a sincere communist to the country’s boldest politician. Tahira also served as a mentor and maternal figure to ZAB’s daughter Benazir whenever the latter sought her advice regarding her personal and political troubles.

I can also humbly admit that Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan and ZAB also played an important if humble part in my own intellectual formation.

Meeting with Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan was one of the abiding memories of my life. Soon after my return to Lahore from Leeds following my MA, I was working on a project on the contributions of the Railway Workers Union to the struggle for democracy in Pakistan. Tahira was an obvious port of call and she not only sat down with me one afternoon at her sprawling Shah Jamal mansion in 2003 to recount her fascinating political journey from colonial India to independent Pakistan, but also suggested me names of fellow communists and journalists to contact for my research. I will never forget the twinkle in her eyes as she laughed and narrated how a group of Vietnamese women, who the DWA were hosting in Lahore, broke out into cries of ‘Pasionaria’ upon seeing her, referring to the name given to a legendary Spanish communist and anti-fascist leader Dolores Ibárruri.

As an idealist Marxist postgraduate student at the University of Leeds in the UK in 2002, the most important chapter of my Master’s dissertation was in fact written on Bhutto. Its title was ‘Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: Bourgeois Socialist Or Populist Demagogue?’ and is a humble attempt to understand Bhutto from the lens of the theory of populism in the conditions of late capitalism in peripheral capitalist societies.

Here is my conclusion from that chapter:

“Indeed, Bhutto evokes fairly accurate comparisons with Peronist Argentina. But the form of state which in my opinion is the most suitable for describing the Bhutto era, whatever the status of industrialization, is the notion of Bonapartism; this is a form of a state where the regime in power vacillates between the interest of competing classes.

Such a leader, because he is not faithful to any one class, will always serve the interests of either when it serves his own interests. Thus, he can never be a cause of revolutionary upheaval of the state in favor of the masses. Therefore, a Bonapartist leader cannot be relied upon to serve the interests of the people; he always follows his own interests, which are seldom at one with the majority. According to Trotsky (1974: 326) “In the industrially backward countries foreign capital plays a decisive role. Hence, the relative weakness of the national bourgeoisie in relation to the national proletariat. This creates special conditions of state power. The government veers between foreign and domestic capital, between the weak national bourgeoisie and the relatively powerful proletariat. This gives the government a Bonapartist character sui generis (of a special type). It raises itself, so to speak, above classes”.

Zulfikar Bhutto made the same mistake of following the Bonapartist route, trying to mediate between both classes (though as opposed to what Trotsky had said, there was no significant bourgeoisie in Pakistan, what of talk of their national character), he ended up siding with the strongest class, but remembered by the weaker class.

Tariq Ali reflects on Bhutto’s failure, and the oligarchy’s gain, “… (Bhutto) faded to construct a strong basic in any class. Instead he gave a special twist to the Pakistani variety of the populism; he sought to compensate for his lack of institutionalized political support by constructing extremely powerful extra-state apparatuses designed to coerce… Once Bhutto had put the state back on its feet, however, he was dispensable, and the army eliminated him at the first possible opportunity”.

Bhutto’s failure was historic; but that of capitalism’s role in spawning such a mass of contradictions had been even larger. It served a dual function: it provided the masses with a fallen martyr and the military another reason to keep coming back from the barracks.”

Though Tahira and ZAB fought for the same causes and on the side of the underprivileged, and their lives intertwined in 20th century Pakistan, one can also say that both fought for a progressive, secular Pakistan which has yet to be realized in the 21st century. Yet, the relative longevity of Tahira and the tragic, early end of Bhutto also point to a basic fact that power without the people ends up consuming the ‘powerful’.

The lives and legacies of both offer a stark contrast in class struggle and its contradictions. Tahira broke away from her class and remained a beloved figure for her commitment to communism, the ideology she imbibed in her teens and never wavered from until in the end. ZAB on the other hand never really broke away from his own class or its interests and kept kowtowing and placating it until the contradiction caused his own downfall, making him a polarizing figure in our history. Or as the French revolutionary Saint-Just had recognized from experience as early as the 18th century when he quipped that, “Men who only half make a revolution are only digging their own graves.” Today, as we celebrate and remember the birthdays of both Tahira Mazhar Ali Khan and ZAB, two of the finest daughters and sons produced by Pakistan, we must certainly dwell on the price and paradox of attaining people’s power – and losing it.