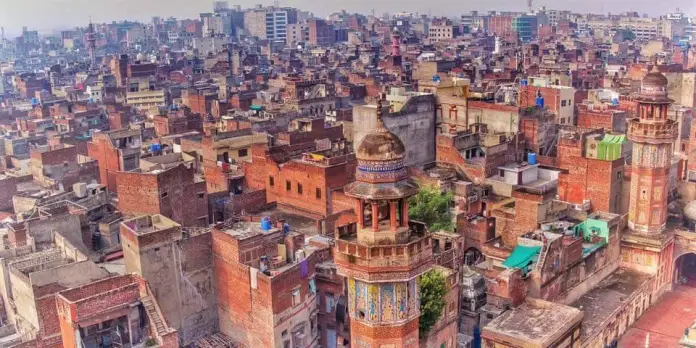

My name is Samina Rashid. My parents always called me by my nick name, Chamma. I am a Pakistani-American woman living in the “me too” era. I came to USA in 1998 at the age of thirty-eight with two small kids. I was born on November 12 1960 at Dr. Sami’s clinic near Government College, The Mall, Lahore.

I am writing the truth about Pakistan, my country of birth, by starting at the beginning of my time there, and ending where I left off. These are my heart felt, first hand, actual life stories. They encompass a plethora and range of emotion, culture, history, politics, family, and humanity, sometimes lack thereof. The objective of these stories is to highlight a journey, sometimes from the eyes of a child growing up in Pakistan, other times a young woman, and later still, a mother, woman, writer and activist who went through the normal and not so normal, from riding a bicycle in GOR 1 and studying at the Convent and Kinnaird, to a young girl who went through dark times which left her in trauma.

Such is the life of many Pakistani girls and women, who experience the clutches of Pakistani culture and society, going from protection and love, to wrath, pain and yes, even rape. Some of these stories get told. Most of them get shoved under the rug. I am a truth teller. I will start at the beginning and go to the end, making no omissions. I will leave nothing out. These are the real tales of my life thus far. If you are weak of heart, please don’t read any further. If you have courage to bear truths, both light and heavy, fair and dark, funny and tragic, then read on and become part of my journey.

It was midnight November 12th 1960 when my mother Sayyada lay on Dr. Sami’s delivery table, waiting to deliver me with the help of forceps.

Meanwhile, some miles away along Lahore’s train tracks, Sayyada’s cousin Abda lay ever so quietly on the train tracks with her three small daughters. She was waiting for the approaching train to relieve her and her children of their pain. They would be delivered from life at the same time I was delivered into it.

We would go into the night on the crossroads of beginnings and endings, without ever meeting each other, but knowing each other all too well and carrying each other inside of us. From Dr. Sami’s clinic, Sayyada, my mother, my Ami, could hear the sounds of the trains passing by. At the gong of midnight, she would hear the train wheels’ screech as she let out one final yelp and pushed as the doctor’s high forceps pulled me out into the world. High forceps helped me begin my journey through life, as they had once helped my Aunt Abda.

As the train wheels crushed the skulls of Abda and her daughters, my skull was trapped between two tongs wrenching me out of Sayyada’s belly. Those forceps did not allow me to say yea or nay to being born. I had no choice in the matter. Abda would become Lahore’s midnight corpse while I would be Lahore’s first midnight child born that November 12th. Our spirits would share an uncanny bond.

I imagine the moment of my conception on an April evening of 1960. My dad would have returned home after yet another drunken night, to the principal’s lodge in Government College, where he unintentionally impregnated an unwilling Sayyada. My parents had not planned for another child this late in their lives. Their older children, Guddo Mamo and Khala Minni, were already in their teens. I was truly an unplanned accident.

They decided to honor the accident and let one last child come into the world. How I have often wished they hadn’t. It would have saved me a lot of pain. Conversely, of course, it would have denied me a lot of pleasure. The night I was born, Nano Sayyada was just about eight months along and was on her way to work at Lahore College for Women. She was in the family’s small green Morris, driven by a dribbling, foul-tempered driver named Miraj. The horse in front of them got spooked pulling its carriage and stood on its hind legs, making the carriage reverberate and come apart as it crashed onto the body of the car. Nano Sayyada was thrown violently forward and back, her pregnant belly hitting the car’s dashboard.

Inside her belly, I bore the brunt of the impact and she went into convulsions from the shock of being hurled into the metal dashboard. I don’t know if an unborn child can record events inside the womb, but to this day, horses scare the hell out of me. I can’t go near them. But whenever I’ve asked Nano if the horse was okay, and she assures me that it was. Ami went into premature labor and was transported-in a Morris with a fuming hood that almost caught fire-to Dr. Sami’s clinic. There she would undergo fourteen hours of severely painful contractions.

After I’d entered the world as a three-pound “preemie,” Dr. Sami chided my mother for having produced a girl instead of a boy. Guddo Mamo, then fourteen, refused to come see me because the household staff told him it was tragic that he did not have a brother.

That’s the good news. The bad news was that less than an hour into my premature birth, my aunt Khala Masooda, whom I would never get to meet because she passed away a few years later due to kidney failure, told my mother to defy Dr. Sami’s orders. The doctor’s orders were to not bathe me, as it would threaten my respiration. As a preemie, if exposed to temperature change, I might not be able to breathe. The clinic did not have ventilators and incubators then, so all they could do was wrap me tightly in towels and keep me as warm as possible.

But Khala wouldn’t hear of not bathing a stinky, swirly, lathered-in-placenta newborn. Not only did it defy Islam, it offended the family’s sense of cleanliness and order which approached a certain genetic level of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Dirt was a curse and had to be eliminated without delay, no matter the consequences. The Freudian transference of guilt about sex may well relate to the neuroses of women who clean everything within their world like demons. Are they expunging illicit thoughts they dare not express by keeping surfaces extra clean? Women in our family were known to get down on their hands and knees to wipe off floor stains, even when their aging bodies couldn’t handle the strain, even when they were about to deliver babies, because babies could not enter a less-than-sterile house. Those were the rules passed down to us by our great-grandmothers. They spent hours of their day attached to mops, brooms, dust pans, and moist wipes. Their world is a dirty oyster that must be scooped out daily: morning, noon and night, using the power of their aching fingertips to remove even the mere shadow of a speck of dust.

Even on her deathbed, my mother told the maid to straighten the sheets before calling it a life. I grew up watching my mother wash and rewash her drinking glass at least three times after staring down at the water to make sure it was clean.

Driven by her cleanliness fetish, Khala Masooda took me into her arms shortly after midnight. She would give me a bath immediately, even if it killed me. It nearly did. I quickly went into complete anaphylactic shock and respiratory distress, turning black-and-blue, heaving for breath because my undeveloped lungs could neither handle the temperature change of a cold November night nor the coal dust in the notorious atmosphere of Lahore, Pakistan.

They rushed to get the nurse to tell her something had gone wrong. Dr. Sami ran back into the labor room, cussing at both women as he began to give me mouth-to-mouth breaths to fill my lungs. He told them I might not make it through the night, whereupon both women cried and took to their rosaries and began to recite the Ayatul Qursi, a prayer that is supposed to help humans out of mortal troubles through the grace of the almighty. I guess there is something to be said about the power of prayer. Mom says I began to turn pink in a few days, from a dark shade of purple-blue. I wouldn’t eat; that is, wouldn’t take milk from breast or bottle. I would take a few drops and just clamp my jaw shut. She didn’t know what to do but kept forcing a few drops of milk into me every few hours to keep me alive. And keep me alive she did. That time. She would fail many of the future keep the-child-alive tests.

Aunt Abda had large, hazel eyes, dark olive complexion, silky, light brown, shining hair. Abda was much younger than Nano, but they had played together in the sunny valleys of Kashmir, and were each other’s best friend growing up. Ami talked about her joyous temperament, how she was playful and loving. They rummaged through the cornfields of the small valley of Kashmir in the 1920s, playing with other village kids, oblivious to the world around them.