The year 1941 was an otherwise bland year for the Indian subcontinent. The main Muslim political party, the Muslim League had passed the historic Lahore Resolution demanding a separate country a year before; while the disappointments of the failed British Cripps Mission Plan and the subsequent Quit India Movement called by Gandhi which further communalized the Indian milieu were still a year away. However, two important deaths took place in 1941 which deeply shook the literary and artistic worlds. The great Bengali polymath Rabindranath Tagore passed away in Calcutta in August at the ripe-old age of eighty, and the pioneering Hungarian-Indian painter Amrita Sher-Gil died on December 5, 80 years ago today in Lahore, aged just 28.

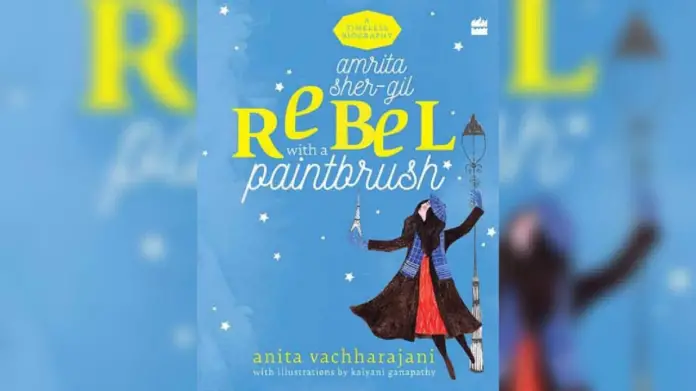

It is gratifying to read and review a new biography of Sher-Gil during the current campaign for the ’16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence’. Rebel with a Paintbrush, as it is called, is the first biography of this path-breaking artist in more than a decade, written by Anita Vachharajani. What distinguishes it from its predecessors is that it is beautifully illustrated as well. While ostensibly marketed as a children’s book, it is certainly readable across the age divide.

Amrita’s story is both astonishing and tragic; astonishing because as a child of two cultures and having lived, worked and traveled in the West in the early part of the 20th century for most of her adult life, she returned to live in her father’s homeland for the last eight years of her short life to paint her best work, which truly made her immortal; and tragic because while she was growing as a painter, she was also getting lonelier as a person despite an apparently successful marriage to the love of her life, and a string of passionate love affairs across the gender divide with people known and not-so-known.

The story begins from a Hungarian village where young Amrita was born in January 1903. The story of Amrita’s parents crisscrosses with the declining fortunes of two empires: the Sikh Empire in Punjab founded by the mighty Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. Amrita’s father Umrao Singh was a beneficiary of the lands given to his father for supporting the British in the War of Independence of 1857. After his wife died suddenly, a grieving Singh happened to visit London where he met his old family friend, Princess Bamba, who was the daughter of the last Sikh ruler of Punjab, Duleep Singh. Princess Bamba wanted to undertake a journey to Lahore to rediscover her roots, and because she did not want to travel alone, she put an ad in a newspaper for a companion to accompany her. The young woman who successfully applied to be Bamba’s companion was Marie Antoinette, a Hungarian pianist. Both got along so well that they made several trips to Lahore. Both Umrao and Marie Antoinette fell in love and eventually married in 1912 in Lahore.

The different cultural worlds of both of her parents produced a happy childhood for young Amrita, but political and economic uncertainties meant that the Sher-Gils had to live out the first seven years of Amrita’s life in Hungary and then move to Simla. Given her childhood proclivities towards art, she was destined to be an artist, but whether a great or obscure one, time would tell. On the return journey to Simla, as the book recounts, little Amrita was privileged to stop over in Paris to visit the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, as well as celebrate her eighth birthday en route!

In Simla, Amrita quickly settled into a bourgeois lifestyle and happily took to her painting. She even accompanied her mother and sister to Italy for 6 months. Those were also the days when Amrita had her run-ins with dull teachers and the stern Catholic matriarchs at the convent where she was enrolled following her return to Simla.

The raw material for Amrita’s later forays into painting realist subjects based on her own surroundings was also laid out here, which transformed her from a mere mimicker of European masters to a truly great artist. As early as 13, Amrita had noted in her diary:

“We went to an Indian wedding where the bride was 13 years old and the bridegroom was 50 and had three wives already. Poor little bride, she did look forlorn as she sat in a lonely corner where around the room sat all the Indian ladies clad in the gorgeous robes of gold and silver and sparkling from rubies, diamonds, emeralds and pearls…”

It was Amrita’s maternal uncle Ervin Baktay who met her in Simla on one of his trips and advised her to ‘draw from life’ just a year later. Amrita would hold fast to this life-changing counsel and never look back.

It was Ervin too who suggested to her parents that she move to Paris, the center of the art and intellectual world in Europe at the time to hone her skills. Paris, the laboratory of the arts, offered Amrita everything from nude models to the company of exciting fellow artists-in-the-making. She also fell in love with a fellow artist Boris Taslitzky. What Paris didn’t offer her though, to her mother’s disappointment, were suitable matches to marry.

Even in Paris, Amrita’s eyes and heart were set in India. One is struck by paintings like Self-Portrait (9) (1930) and Hungarian Gypsy Girl (1932) from her European sojourn.

If Paris broadened her art horizons, it was her summer vacations in Hungary which gave Amrita her lover, soulmate and the only man she was ever going to marry, Victor Egan Junior, a cousin from her mother’s side. Though it has remained unclear to this scribe even after reading this book, what his real role in Amrita’s life was, as he has even been accused of murdering Amrita, whether out of a jealousy for her many affairs or to abort a pregnancy.

Back in Paris, Amrita painted and collected further prizes and accolades from the stuffy and closed French art world. The standout painting from this era was Study of Model (3) (1933), a portrait of a professional painter’s model who was poor and struck down with tuberculosis. It is hard not to be intrigued by the poor woman’s misery and resignation looking at the painting and connecting its theme with her later work which she did in India.

But tired from the monotonous art world of Paris, destiny was calling Amrita back home to India, which she did in 1934. Her art truly became Indian from here on. One just has to look at her paintings like The Little Girl in Blue (1934). One can say that Amrita Sher-Gil reached the same conclusion about the direction of her art – or Indian art as it existed at the time – which her literary contemporaries like Munshi Premchand had reached about the state of Indian literature, and which would lead to the formation of the Progressive Writers Association in 1936. The standards of art would have to change, but not the artist! Amrita was not alone in being the harbinger of change in the art world; there were fellow painters like Chughtai, Jamini Roy and M.F. Hussain who would outlive Sher-Gil and become legends as the 20th century marched on. Amrita was beginning to be noticed in the Indian art scene, but she was also very headstrong and self-opinionated, sending back her prize money to the Simla Fine Arts Society along with an angry letter when she felt her more modern art was under-appreciated. This was also the time when she regularly picked up a host of lovers from Malcolm Muggeridge to Badruddin Tyabji, though her ‘nymphomania’ is not even casually hinted here.

On Amrita’s significant trip to south India which yielded one of her most important series of works, she told off her generous host, the Prime Minister of Hyderabad Deccan for not owning a Cezanne, Van Gogh or Gauguin, but also made new friends and admirers like the freedom-fighter Sarojini Naidu and a certain Jawaharlal Nehru.

In 1937, just four years before her tragic end in Lahore, this same city was the scene for one of her greatest triumphs – her exhibition at the elegant Faletti’s Hotel. A few months later, she was to marry her cousin Victor in Hungary, to the great opposition of her parents. After the marriage, the couple was no more welcome at the parental home in Simla, so after a couple of anxious years, they finally settled down in Lahore at the illustrious Ganga Ram Mansion. This was also the time when Amrita experimented with animal art; in fact her final unfinished painting on which she was at work right till a few days before her death featured four buffaloes and a crow.

Art critics and aficionados of Amrita’s work all recognize the sadness and misery on the faces of Amrita’s well-chosen subjects in her paintings, but how many also realize, then or now, that this could also be showing the artist’s own misery, anguish and loneliness in her final years? That she was progressing as an artist but dying as a living, breathing soul?

It all ended for Sher-Gil in Lahore on a coma-fueled December night, just as it had for Pakistan’s national poet three years prior in that very city; in fact, Lahore would claim three more young victims in the succeeding decades: Saadat Hasan Manto, Chiragh Hasan Hasrat and Saghar Siddiqui all went early. She was cremated on the banks of the Ravi a couple of days later, despite being an atheist. And after Amrita Sher-Gil’s other famous namesake, the Punjabi literary icon Amrita Pritam left Lahore in the communal hysteria of 1947, Lahore would never again have another Amrita.