Elia Jaun kuch nahi karta

Sirf khushboo mein rang bharta hai

(Elia Jaun does nothing

Just fills fragrance with colouring)

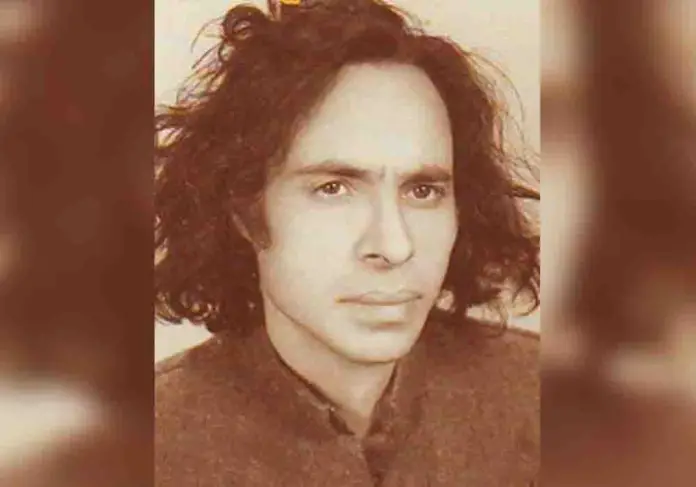

Just fills fragrance with colouring. A special thing regarding Jaun Elia which has often come before me is that when people unaware of Jaun hear his name, they neither consider him a poet of the Urdu language nor a Muslim. It is an opportunity for surprise that a few people on the basis of ignorance consider him feminine and for these ignoramuses he is some European poetess when the reality is that Jaun Elia’s name is also unique like his personality.

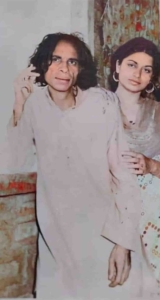

Of late, this ignorance coupled with jealousy and mischief has taken the form of a pandemic so much so that on November 26 this year, Khalid Ahmed Ansari, a compiler of Jaun’s posthumous poetic collections was forced to clarify about a photograph which has been doing rounds on social media with countless posts in the form of a poisonous text under the caption ‘The beautiful delicate girl standing behind is actually Zahida Hina…’ This is definitely part of a well-thought propaganda campaign about Jaun which seems like the mischief of demented orphans who are frightened of the fame and literary stature of Jaun Elia.

The superficial information of the writer of this text can be gauged from the fact that he deems the woman in the aforementioned photograph to be Zahida Hina; whereas this photograph is of Jaun Elia’s niece Rukhsar who lives in Delhi and is the daughter of a big name of the Indian film industry, Kamal Amrohi. It dates from Amroha in 1975. Apparently, every so often someone or the other sends this photograph on WhatsApp/Messenger asking ‘Is this Zahida Hina?’ Maybe next something else is said by putting the photograph of another maternal or paternal niece beside him. So lovers of the poet are requested to ignore such texts and find him in his verses because in future the use of technology can also come to the fore.

Jaun Elia’s first poetic collection Shayad (Perhaps) came to the fore in 1990 when the major part of his life had passed. Despite the delay in publication of the collection, he became very popular and famous in the mushairas held at home and abroad. Perhaps this is the very reason that he was deemed a poet of mushairas and even literary critics did not give him satisfactory attention. Jaun Elia himself too always had the same complaint that he did not attain the fame which his contemporaries were getting at that time. One reason for this remained that the verses of Jaun Elia could not be published on time. But the greatest attribute of art is indeed that it remains alive and does make its greatness very much felt whether that feeling happens in the lifetime of the artist or afterlife. The acknowledgement of Jaun Elia’s greatness was made in his life; although the importance of Jaun’s creative ability is being acknowledged in the present time, so there is a need for a detailed review of his thought and art. This tribute is a humble effort to fulfill that need on Jaun’s 90th birthday.

It is said about a lot of poets that they are poets of a unique voice but when this very thing is said for Jaun Elia, then the heart and sight unhesitatingly accept, as if this holds true for him with all its meaning. In the crowd of Urdu poets, his voice is unique. The individuality of his voice grants him a distinctive grandeur.

Jaun has a feeling of the effect of his voice and a perception of his individuality; as if an intuitive knowledge of his self-esteem. He does not give importance to any of his contemporaries and declares:

Khatam hai bas Jaun par Urdu ghazal

(With Jaun has just ended Urdu poetry)

What to talk of contemporaries, he does not regard even the poet of poets, he calls him a shaveir (minor poet) with contempt, in fact insults him to such an extent that:

Nahi imlaa durust Ghalib ka

Shaifta ko bata chuka hoon main

(The dictation of Ghalib is not accurate

I have told this to Shaifta straight)

So many poets tried to imitate him after being influenced with his voice but were not successful. If someone would recite verses in his meter, he would get upset at him; he says about the failure of those who steal his writing style:

Yeh hai ik jabar, ittefaq nahi

Jaun hona koi mazak nahi

(This is a fate, not a contingency

Being Jaun is no pleasantry)

It is not a pleasantry to remain alive among continuous failures, deprivations and compulsions. Jaun opened his eyes in an opulent feudal environment, 90 years ago today on December 14, 1931. His childhood and boyhood were spent in this very milieu. He acquired the Persian language and literature; poetry and literature cast a shadow on him, and began to be expressed by his pomegranate lips; youth and beauty; flirty poetry; youths and beauties began to fall in love with him. The entire feeling of happiness began to bloom over him.

Hai muhabbat hayat ki lazzat

Varna kuch lazzat hayat nahi

Kya ijazat hai aik baat kahoon

Voh magar khair koi baat nahi

(Love is the taste of life

Life is not at all taste otherwise

Am I permitted to say something

That, if, well, never mind)

Meri jab bhi nazar padti hai tujh par

Meri gulfaam jaan-e-dilrubai

Mere ji mein aata hai ke mal doon

Tere gaalon par neeli roshnai

(Whenever you come into view

My rosy heart-stealing beloved

I have an urge of rubbing

Blue ink upon your cheeks)

Paseene se mere ab toa rumaal

Hai naqd-e-naaz-e-ulfat ka khazeena

Yeh rumaal ab mujh ko bakhsh dijiye

Nahin toa laiye mera paseena

(With my sweat the handkerchief

Is a treasure of the wealth of love’s coquetry

Grant me this handkerchief now

give me back my sweat)

Sharam dehshat jhijak pareshani

Naaz se kaam kyun nahi leteen

Aap, voh, ji, magar yeh sab kya hai

Tum mera naam kyun nahi leteen

(Shame fear hesitation distress

Why don’t you resort to playfulness

You, he, yes, but what is all this

Why don’t you call my name, mistress)

The ghazals, poems and quatrains sunk in the pleasure of his first love meaning Fareha are the memorial of his happy period.

Jaun was still eighteen years old that suddenly the scene of the drama changes, meaning the country was partitioned, populations began to transfer from here to there amid killing and looting, house upon house began to become desolate and quarter upon quarter began to empty. City upon city became quiet, desolation began to dance in the bustling lanes and quarters. Silences began to guard the flourishing squares. The remaining was made up for by the end of landlordism in 1952. Jaun’s beloved Fareha migrated to Karachi and got married there. What effect this would have had on the sensitive heart of a born poet like Jaun, one can get from studying his poetry.

All the three elder brothers of Jaun had become migrants one by one, the death of his parents had very much broken Jaun; now he was left alone, loneliness began to bite him, all the near relatives had relocated. Jaun dearly loved every particle of the dust of his land; its lanes and quarters ran through his entire body. For him migration was not easy but reluctantly, he was forced to separate from his beloved country, he too settled in Karachi but the cries of separation from the homeland are heard in his poetry even today.

After reaching Karachi, the hardships of economic problems too affected his sensitive heart; a scholar like Jaun should have obtained a good service in some educational institution, but by disposition he was not of this kind. The fire of the belly cannot be quenched by mere ink-stains. He got support from the editorship of magazines to quench it. When he became the editor of a magazine, he became the disciple of a hennaed hand. A heavy drinker took the oath of allegiance at the hand of a Zahida (ascetic) and tied to a vow of faithfulness forever. They got together, the difference in the natures of both began to be clear. After the blooming of three flowers, the fourth flower bloomed in that both got separated. Jaun became alone despite having a full world, this is the accident of 1980. Fifty years meaning two-thirds of his life had passed. The children Fainaana, Sohaina and Zaryoun remained with their mother. Jaun kept burning in the hell of tortuous solitude, his condition became like a semi-lunatic. Had his kind friends not supported him, he would have passed on in this very state. In the foreword to his first collection Shayad, Jaun writes:

This is an account of 1986, my condition was seriously deteriorating since the last ten days. I used to sit scared in a corner of a semi-dark room. I felt scared of the light, sounds and people. One day my dear brother Saleem Jafri came to see me. He had come to Karachi from Dubai a few days ago. He said to me Jaun bhai, I will not let you live the life of escape and aversion. You have shown me the dreams of revolution, victory of the masses and classless society since my boyhood. I said, do you know what agony I have been afflicted by years after years? My brain, is not a brain but embers. The eyes, which are aching like wounds. If I fix my vision on paper to read or write for a few seconds even, such a condition passes as if I have a complaint of conjunctivitis and in the summer month, one is reading hell within hell.

This is a light background of Jaun’s poetry that is why he said to his imitators:

Yeh hai ik jabar, ittefaq nahi

Jaun hona koi mazak nahi

(This is a fate, not a contingency

Being Jaun is no pleasantry)

Jaun published a selection of his poetry in his lifetime with the title Shayad in 1990, after him his abandoned verses along with all the good and the bad were published in many collections Yani (Because), Goya (As If), Gumaan (Doubt); essays in great number were written in Indo-Pakistan on his personality and poetry and collections of those essays were published.

The ascent of Jaun Elia’s life had occurred in comfort. But the circumstances changed in a flash. Economic compulsion, failure in successful love, distance from one’s own, separation from homeland worsened Jaun’s psychology! Yes sir, while reading his poetry it feels that it is the melancholic screams and cries of the deprived heart of a worsened psychology:

Chaba len kyun na khud apna hi dhaancha

Tumhen raatib kyun muhayya karen hum

Nahin dunya ko jab parva hamari

Toa phir dunya ki parva kyun karen hum

(Why should I not chew my own skeleton

Why should I supply you with the food ration

When the world does not pay us attention

Then why should we care about the world)

Mustaqil bolta hi rehta hoon

Kitna khamosh hoon main andar se

(When I talk I am incessant

From within I am so silent)

Kal dopahr ajeeb si ik be-dili rahi

Bas teeliyan jala ke bujhata raha hoon main

(In the afternoon yesterday the heart was in a strange anguish

I have just been lighting matchsticks, then making them extinguish)

Kya takalluf karen yeh kehne main

Jo bhi khush hai hum is se jalte hain

(To say this, why should we be so ceremonious

Whoever is happy, of him we are envious)

The greatest agony of Jaun’s life is separation from Fareha and absence of the homeland, which kept running like a saw within his chest until the last breaths of his life, the bruises from which his poetic form is bloodied.

About his migration, it can be said that the anguish of migration occupies a prominent place in Jaun Elia’s life and poetry. He forcibly migrated due to economic needs and this agony proved to be a sore for him, due to which the tragic tale of migration is present in his poetry. He had unlimited love for his dear country, which he has displayed everywhere in poetry through the beautiful painting of the streets, shrines, streams, schools, etc. of his homeland. After reviewing Jaun Elia’s poetry, the thing is clear that the biggest mover of his tragic poetry is the agony of migration, which left his life involved in a further perilous condition. The intensity with which he felt this agony, he described it on an emotional level in words too with the very same intensity:

Is gali ne ye sun ke sabar kiya

Jaane vaale yahan ke the hi nahi

(Hearing this, that lane became patient

Those who left were not its resident)

Is samandar pe tishna-kaam hoon main

Baan, tum ab bhi beh rahi ho kya

(I am thirsty upon this sea

Baan, are you still flowing merrily)

Shaam hui hai yaar aye hain yaaron ke humrah chalen

Aaj vahan qavvali ho gi Jaun chalo dargah chalen

(It is evening, the companions are here, let us accompany them

Jaun let us visit the shrine, there will be a night of devotion)

Hence Jaun Elia enriched Urdu poetry with a new thought, new tone, new melody and style and new manner and mood. I will conclude with Jaun’s own couplet:

Khatam hai bas Jaun par Urdu ghazal

Us ne ki hain khoon ki gul-kaariyan

(With Jaun has just ended Urdu poetry

With blood he has created embroidery)

*All translations from the Urdu are by the author.